Florida Today

August 26, 2020

Some of the deadliest weapons ever made by humankind are right off our shores, deliberately dumped at the bottom of the ocean from Delaware to Florida.

Fifty years ago this month, servicemen sank — on purpose — a 442-foot World War II freighter loaded with 12,540 rockets of sarin nervegas and one container of even deadlier VX nerve gas. She was sunk 283 miles due east of Cape Canaveral. It was all part of a military weapons disposal plan, supposedly the last of its kind.

The lethal cargo aboard the scuttled LeBaron Russell Briggs was the final “known” major cache of chemical weapons that America dumped at sea. Her cargo of obsolete nerve gas from the Korean War sank three miles deep in just eight minutes, slamming the seafloor at 25 mph and bringing to a spectacular end the controversial practice of dumping chemical weapons offshore.

But the Briggs is just one of many ships loaded with chemical and other toxic weapons lying on the ocean floor in the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico.

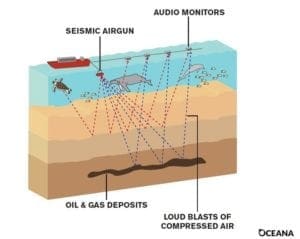

Experts long feared it was only a matter of time before the thin metal casings containing the toxins corroded, releasing their poisons. But now another fear has taken hold: the search for new oil fields could inadvertently unleash the banned poisons, threatening marine life, the food web and ultimately us.

The Today paper carried a front page photo in August 1970, when the military sank an old World War II ship filled with thousands of rockets of chemical weapons, about 283 miles east of Cape Canaveral. FLORIDA TODAY Archive

Speculators seeking new fossil fuel deposits are preparing to fire seismic airguns at the bottom of the ocean along the Eastern Seaboard.The guns are powerful enough to send sound waves miles into the earth’s crust. The blasts, environmentalists warn, could easily rip through rusting drums and missile casings.

“We’re having to come to grips with what we did in the past, to do what we want to do in the future, and you don’t do that with blinders on and tap dance through a minefield,” warns James Barton, a disposal expert based in Norfolk, VA.

Barton served in the Navy as an explosive ordnance disposal technician and has been diving on and cleaning up lethal underwater weapons for four decades.

Florida like other states has no law or policy to force oil explorers to prove definitively there’s no explosives or other dangerous waste where they plan to survey the sea floor before they start. Attorney generals from at least nine states (but not Florida) have joined a federal lawsuit to stop the air gun tests — a case that might get its day in court this fall.

Industry officials insist the areas to be surveyed will be relatively small and that they are armed with the technology and know-how to avoid sunken dangers. They also insist that seismic testing does not pose the danger critics claim. And they point to the potential for a massive economic shot-in-the-arm. The American Petroleum Institute, an oil and gas industry trade and lobbying group, points to a 2018 study by Calash and Northern Economics that projected oil and gas drilling in the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf could generate $260 billion in spending over 20 years, and almost 265,000 jobs nationwide.

Meanwhile, the Department of Defense insists the buried poisons are not as vulnerable as environmentalists warn.

What all’s out there?

Jim Barton, an underwater munitions expert, he circa 2003, helps conduct a radiological and chemical assessment of a former U.S. Navy bombing range off Puerto Ricco’s coast. James Porter, University of Georgia

No one knows exactly how many of these mysterious “ticking time bombs” scenarios lurk in our depths. Some dump sites lack coordinates. Ocean currents moved others.

According to a U.S. Army report in 2001, the U.S. military dumped chemical weapons agents and munitions in oceans throughout the globe at least 74 times between 1918 and 1970, including 32 times off U.S. shores.

Barton warns of speculators accidentally blasting open countless poisonous Pandora’s boxes of forgotten chemical or radiological weapons along the ocean floor, the remnants of which storms could even wash ashore.

The risk that could pose is not lost on Florida’s multi-billion tourism industry and coastal property owners.

More than 20,000 shipwrecks surround the United States. Some of the vessels are military and contain untold catches of weapons. NOAA

“You just can’t take the word of the seismic testing and oil industry: ‘Oh no, it can’t possibly hurt,’ ” said Frank Knapp, president and CEO of the South Carolina Small Business Chamber of Commerce, one of the entities suing in federal court to stop the surveys.

“We used to dump nuclear material off our shore back in the day in the ’40s and ’50s because we thought it was safe,” Knapp added. “That’s out there, too, in drums. They don’t have a record of where they all are.”

The same holds true for chemical and all other underwater weapons of mass destruction, he said.

“It’s literally hundreds of tons of this stuff, and nobody really knows exactly where it is,” Knapp said. “Who wants to swim in that water?”

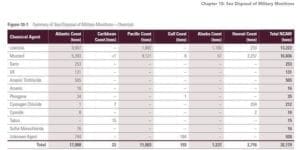

The military left thousands of tons of chemical weapons along the ocean floor. 2009 Defense Environmental Programs Annual Report to Congress

After World War II, the military ordered coastal commandants to get rid of their “field of steel” — all the bombs and other weapons headed toward Europe or confiscated from the enemy, that were no longer of use, said James Porter, a professor emeritus of ecology and marine science at University of Georgia.

“A vast majority of ‘the field of steel’ was dumped in the ocean,” Porter said. “That process was very poorly documented.”

Early on in the process, sailors who dumped chemical weapons at sea were so afraid of what they had that they often jettisoned their deadly cargo before the ship’s lines were even cast off from the dock, Porter said, or well before they reached designated disposal sites. So there are many munitions scattered well beyond the boundaries of even known ocean disposal sites.

“You can follow this line to where they were supposed to dump it,” Porter said. “They were terrified of what they had on board.”

But should we fear it now?

Without accurate records of exactly what weapons lurk along the ocean floor and where, no one knows to what extent toxic chemicals might be leaking, or the health and environmental risks the weapons pose.

But everything in the U.S. arsenal was at some point disposed of at sea, Barton says. And there is anecdotal history of chemical weapons washing up and hurting people. Even a small fragment of a chemical weapon that washes ashore looking like a rock can cause severe chemical burns.

Barton cites a 2012 incident near Camp Pendleton, in California, when hours after a mother drove home from the coast with beach “rocks” still in her pocket, her pants “caught fire” while standing in her kitchen. Both she and her husband were hospitalized, and their hardwood kitchen floor was damaged.

According to media reports at the time, Camp Pendleton officials said there was no evidence that any military materials were involved, despite the history of white phosphorous munitions being expended in that immediate area, and white phosphorous being a man-made compound produced almost exclusively for military use.

Barton says the Atlantic coast may harbor even worse risks, given they are home to some of the largest known deposits of sea-dumped chemical weapons in the world.

“We have a history of dumping those types of materials in large blocks of concrete,” Barton said. “Gas-filled rockets are leakers, wherever they’ve been stored there’s a problem with them.”

Five companies want to survey the Atlantic Ocean for oil and gas, using powerful air guns. ION GeoVentures

Middlebury College’s Center for Nonproliferation Studies (CNS), has mapped known chemical weapons dump sites worldwide.

Their map includes another site off Canaveral, not that far from the LeBaron Russel Briggs. As part of Operation Geranium, crews scuttled the SS Joshua Alexander in December 1948, which carried 3,711 bulk containers filled with lewisite, along with 60 lewisite-filled mines, about 300 miles east of Florida, the site says.

Screenshot of CNS’s chemical weapons dump site map. CNS

After activism and extensive media coverage, in 2006 Congress directed the U.S. Department of Defense to study the threat from underwater munitions. As a result, in a 2016 report to Congress, based mostly on research off the Island of Oahu, in Hawaii, DoD concluded “sea-disposed munitions, which have become part of the ocean environment and also provide critical habitat to marine life, do not pose significant harm when left in place.”

The report went on to say: “Removing or cleaning up munitions sea-disposal sites would have more serious effects on marine life and the ocean environment than would leaving them in place.”

DoD concluded the potential health effects from sea-disposed munitions in U.S. coastal waters “appear to be minimal.” And recovering munitions, “would likely result in a rapid release of munitions constituents that could cause more harm than would otherwise occur as the munitions continue to deteriorate over time,” the report said.

Barton and Porter call DoD’s conclusions a whitewash.

“It was an absolute fraud,” Barton said. The seafloor in the area of the Hawaiian study is “carpeted with bombs,” he added, but the study looked at “the only place where they couldn’t find something.”

In 2017,Barton coauthored a study for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that countered DoD’s findings. His conclusion was stark.

“The doctrine of denial surrounding the ecologic influence of underwater munitions serves the interests of no one, and can be altered only after the issue of liability has been addressed,” Barton’s report to CDC said. “When considering this, it is important to recognize the U.S. Department of Defense does not make policy, but dutifully carries it out.”

Underwater weapons way worse in Puerto Rico

In 2003,Porter found several compounds in marine sediments and organisms near weapons dumps off Viques, Puerto Rico that are only associated with munitions — smoking guns of sorts. The chemicals are also suspected to be linked with several excess rates of cancer there.

Porter investigated underwater unexploded ordnance on Viques, Puerto Rico, testing marine sediment and organisms. He tested the island’s waters for radioactive material near the sunken USS Killen, a World War II-era destroyer the Navy used as target practice for missiles.

He said he found the canary in the coal mine, hinting at similar scenarios that likely surround other underwater weapons dumps.

“This investigation revealed that every animal tested on the seaward reef of Vieques near unexploded ordnance (UWUXO) contained at least one carcinogenic compound leaking from the submerged bombs, bullets, and artillery shells,” Porter wrote to federal officials in a July 2018 affidavit supporting an injunction on seismic testing near munition dumps.

Seismic testing can disrupt, dislodge, and destroy the integrity of munitions casements, Porter says.

“You’ve got to have a completely independent analysis both of the risk and the threat,” he said.

A significant sinking

The Briggs was the last ‘known’ chemical weapons dumped at sea, and it was right off Cape Canaveral. Such Liberty ships — the ones that German U-boats didn’t sink — delivered the weapons that Europe needed to win World War II.

The Briggs’ last weapons delivery was 282 miles off Cape Canaveral.

Built in Panama City during World War II, the Liberty ship LeBaron Russell Briggs was named after the president of Radcliffe College and the National Collegiate Athletic Association.

The ship was turned over to the U.S. Navy in July 1970 for use in Operation CHASE, which stood for “Cut Holes And Sink ‘Em,” according to media and other historical accounts.

Environmentalists fear seismic air guns could harm dolphins, whales and other wildlife. Oceana

The LeBaron Russell Briggs and the CHASE operation drew protests and widespread media attention in the summer of 1969, as public sentiment turned against the Vietnam War, and up until the ship’s Aug. 18, 1970 sinking.

This August 15, 1970, edition of the Today paper ran a photo showing the huge safety valve on the Liberty ship to be sunk with deadly nerve gas 283 miles off Cape Canaveral. Tammy Moon, Brevard County Libraries

FLORIDA TODAY (called Today at the time) ran several Associated Press stories of the controversy. One described the longshoremen in Sunny Point, N.C. loading the 418 steel-encases vaults of nerve gas aboard the ship as the controversy ensued. A federal judge in Washington, D.C. ordered a hearing after then Florida Gov. Claude Kirk and the Environmental Defense Fund sued to stop the ship’s sinking and to force the Army to prove it had chosen the safest site and all possible environmental risks had been considered.

Two Brevard groups rallied in the days leading up to the sinking, including students, professors and the Association for Concerned Taxpayers.

“We believe that this dumping of deadly nerve gas could be the greatest ecological blunder mankind has ever perpetrated upon nature,” the students said in a petition to several members of Congress, according to one AP article at the time.

A tropical depression delayed the sinking — only for a day — but a federal court would not.

The Bahamas Cabinet voted to lodge a strong protest against the dumping.

It was all to no avail.

The Today newspaper ran several stories back in 1970 the days leading up to the military’s sinking of a ship filled with chemical weapons about 283 miles due east from Cape Canaveral (then called Cape Kennedy). A lawsuit failed to stop the sinking. Tammy Moon, Brevard County Libraries

A convoy that included a destroyer escort, a Coast Guard cutter, and a backup tug, hauled the Briggs and its deadly cargo from North Carolina. The Briggs’ only passengers were several caged rabbits used to determine if any of the deadly nerve gas was leaking.

According to a New York Times account at the time, Army chemical experts had concluded the nerve gases were already unstable, “near the danger point” and dumping them at sea was the safest option.

“They believe that some of the gas has been leaking for months inside the 418 steel‐jacketed vaults containing the rockets and it was just matter of time before some of the gas seeped into rocket propellant and detonated,” the Aug. 19, 1970 Times article reported.

The Naval Ordnance Lab monitored the sinking with hydrophones and tape recorders. From a recording made 2,000 feet from the submergence location, they concluded that “there was no significant release of nerve gas during the plunge to the bottom.”

Most of the Briggs’ nerve gas was expected eventually to leak as the concrete and steel coffins eroded and endured the extreme pressure of 7,200 pounds per square inch at three miles beneath the sea. Chemical experts at the time assured the sarin nerve agents would be neutralized by the salty ocean water and rendered harmless within hours.

Nonetheless, the Briggs’ controversial sinking set the stage over the next few years for federal legislation and an international treaty that banned dumping chemical, nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction in the ocean.

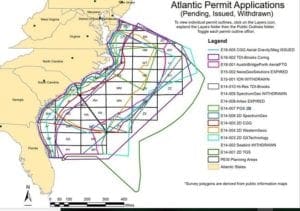

One map on the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s site shows proposed areas for seismic surveys some 400 miles offshore, far enough for the surveys to encounter old military waste dumped at sea decades ago. BOEM

Florida’s D-day training left untold hazards for oil speculator

Legal battle over ocean drilling

Now there’s a possible new threat to the underwater weapons.

Under seismic survey proposals being considered by the federal Bureau of Ocean Energy Management – the lead regulator of oil and gas exploration – ships would tow arrays of seismic airguns, which produce compressed air bubbles under extreme pressure to create sound. Hydrophones towed near the surface record sound that bounces back from the ocean floor to create a 3-D image of geological formations that hint at oil or gas deposits deep in the seabed.

But they are facing a battle.

On August 18, 1970, a freighter ship was sunk 283 miles off Cape Canaveral, filled with thousands of rockets of nerve gas and other chemical weapons. Google Maps

In July, the U.S. House of Representatives passed legislation to block expansion of offshore oil drilling activities in the Atlantic, Pacific, the Arctic and the eastern Gulf of Mexico for fiscal year 2021. If enacted, the legislation would stop the Trump administration’s efforts, announced in 2018, to open almost all federal waters to offshore drilling.

In January, conservation groups filed a lawsuit in federal court in South Carolina to stop the seismic surveys and await a hearing date, which is expected as soon as this fall.

Meanwhile, the American Petroleum Institute, an oil and gas industry trade and lobbying group, warn jobs are at stake.

Frank Knapp, president-CEO of the South Carolina Small Business Chamber of Commerce, speaks at a press conference warning about offshore drilling. Courtesy of Frank Knapp

API says more drilling would likely encourage economic growth, manufacturing and investment, create thousands of additional U.S. jobs, and strengthen our national security.

The 2018 study Calash and Northern Economics prepared for API projects Florida would see yearly spending of more than $485 million due to the Atlantic offshore oil and natural gas industry by the end of the 20-year period, with spending primarily focused on operational expenditures and engineering. Employment in Florida due to spending supporting Atlantic offshore oil and natural gas development could top 8,000 jobs by the end of the 20-year forecast period, the study found.

Industry officials say the risks of surveying for oil and gas have been overblown.

“Assertions claiming proposed Atlantic seismic surveys pose a risk of triggering unexploded bombs and/or the release of toxic chemical and radioactive waste are patently false,” Gail Adams, spokeswoman of the International Association of Geophysical Contractors (IAGC), said via email.

“This issue has never been a concern anywhere in the world,” Adams said. “Seismic surveys have been conducted around the world for many decades with no scientific documentation of any seismic survey causing the initiation of explosions or the compromise of storage containers containing chemical or radiological waste.”

Adams said the seismic surveys release compressed air at pressure levels far below the energy required to activate explosive materials or structurally damage waste containers. “Even when directly over abandoned ordnance or waste disposal areas, the energy from the sound source is insufficient to present a risk of cracking or damaging containers or activating explosive materials,” Adams said.

But drilling opponents counter that any potential economic benefits from drilling pale in comparison to the state’s $28 billion tourism industry, which oil exploration of drilling accidents could put at risk, not to mention the sport and commercial fishing industries.

Knapp, Barton and others point to less destructive alternative technology to explore for oil, and advocate a renewed effort to find cleaner sources of energy.

“To rely solely on the advice of itinerant oil speculators to judge whether or not their use of high powered acoustic cannons directly above federally generated hazardous waste deposits threatens local economies, is an abdication of due process,” Barton said. “It also represents a gross disservice to the sacrifice and commitment by existing stakeholders and vital commerce, that has already built a thriving economy along the entire eastern seaboard of the United States.”

Florida could be a template that other states follow, ushering in more state and federal oversight, Barton says. “The people in the oil business are not in the business of munitions,” he said. “The industry are not going to be the ones that regulate themselves.”

The easiest way to avert their disruption and dispersal of toxic waste is to establish exclusion zones for seismic testing over ammunition dumps, Barton said.

He would like to see the federal government force companies to first run non-destructive technologies like towed magnetic arrays or underwater autonomous vehicle over exploration areas to find the true margins of munitions dump sites before allowing any seismic surveys.

Unlike issues such as plastic pollution, undersea weapons doesn’t get as much attention as other ocean environmental risks, such as plastic pollution, Porter says.

“We do have very serious environmental problems,” he said. “I feel personally, as a marine ecologist, this is one of those serious problems.”

Jim Waymer is environment reporter at FLORIDA TODAY.